Although the focus of this text is on the price effects of tariffs, that might be seen as unfair as that is just looking at the direct negative effect of tariffs (domestic prices rise). We will look at two broad justifications for imposing tariffs. We will start with the simpler argument: tariffs can be used as a major source of revenue to replace income taxes. This is a fringe belief among some free marketeers that President Trump picked up on. The more conventional justification for tariffs is that they are a form of industrial policy (to boost the manufacturing sector). Unfortunately, these theoretical justifications are somewhat tangential to the actual tariff policies of President Trump’s second term — neither objective could be achieved by his erratic tariff rate changes.

(Note: this is an unedited draft section that may go into a chapter on tariffs in my inflation primer, with the second part to show up next. Once the price impact of tariffs hits, I will be able to discuss the price effects. At the time of writing, price changes are still anecdotal, as supply chain disruptions and tariff pricing has not hit most goods currently on sale.)

Tariffs for Revenue

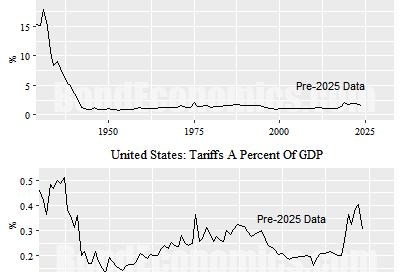

The top panel in the above figure was exciting for some free market supporters in the United States. In it, we see that tariffs represented just over 15% of U.S. Federal Government revenues near the start of the data in 1929 (which is from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis — the BEA). It is even more exciting if we used other sources that take the start of data to the early 1800s, where tariffs represented almost all of the Federal government revenue. In fact, the entire “theory” that tariffs could replace income taxes relied on looking at the top panel of the chart, and believing that it would be possible to “turn a dial” and bring back the tariff revenue share to its 1890 level.

The bottom panel explains why I am much less excited about tariff revenue, as it shows tariff revenue as a percentage of U.S. GDP. Tariff revenues hit 0.4% of GDP in 2022 (which was the peak of recent data before 2025, which was not available at the time of writing). That is not far off from the peak in the 1930s (0.5% of GDP). However, tariffs as a percentage of total revenue (top panel) were still near the rock-bottom levels that started in World War II. The explanation is straightforward: tariffs were only a significant proportion of total Federal revenues a century (or more) ago because Federal revenues were much smaller.

On multiple occasions early in 2025, President Trump made meandering remarks to the effect that the 1890s were a golden era for American capitalism. (These remarks were either buried in ephemeral social media posts or rambling asides in press conferences, which makes it difficult to offer a definitive quotation.) One key advantage in his mind was the reliance on tariffs, and not the income tax as the source of revenue. The first version of the income tax was introduced from 1861-1873 as a reaction to the American Civil War. In the decades that followed, income tax variants were proposed but faced legal challenges. The “modern” version of the income tax was reintroduced in 1913 after a constitutional amendment. Given the hatred of the income tax by rich Americans, the aspiration of “going back to 1890” picked up a few other backers.

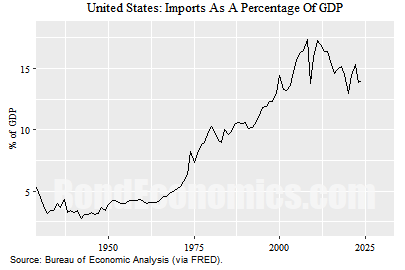

The sustainable revenue share of GDP from tariffs is going to be quite limited for the United States. As shown in the figure above, imports were 14% of GDP in 2024, but were much lower in the high tariff era of near the start of the data (1929). The current level of imports partly results from American firms using international supply chains, such as the auto industry (where some input processing involves crossing the American/Canadian/Mexican borders multiple times). A high tariff rate makes such arrangements non-economic — which means that anything other than extremely low tariff rates will cause a contraction in imports as supply chains are straightened out to avoid crossing international borders. The rapidity of the tariff ambush — and the widespread belief that the tariff policy will be reversed — might allow high tariff rates to coexist with a “high” import share of GDP for a year or so, but sooner or later, firms would react to the higher tariff rates if they are kept in place.

If the United States somehow ends up with an average tariff rate of 20% and a 10% import share of GDP, tariff revenues end up at 2% of GDP (although I would guess that the average tariff rate would have to be 10% or less to sustain an import share of 10%). Although the dollar amounts might impress people who are unfamiliar with government finances (especially when you add up 10 years worth of revenue, which is the standard way of presenting dollar amounts in American political media1), 2% of GDP is still not going to be significant when compared to the current total receipts that are around 18% of GDP. The only way for tariffs to be the predominant share of revenue is to shrink the Federal government significantly (in the ballpark of 5% of GDP) — which even the Republicans in early 2025 have been unable to do.

Although the conservative project has a long history of fantasising about returning to some earlier golden age, thoughtful conservatives were at least slightly aware of the intervening history between the present and said golden age. In this case, going back to the 1890s requires us to put the genie of the First World War back into the bottle — which is largely impossible. The First World War shattered the earlier political systems that made the extremely small government of the 1890s sustainable. Popular economic discussions underplay the effects of the First World War (for example, explaining the entire collapse of the Weimar Republic solely by its hyperinflation). Mass politics pre-1914 are a pale shadow of their post-1919 incarnations. The book The Long Shadow by David Reynolds is one recent overview of the political and cultural aftereffects of The Great War.

Aside: Functional Finance

Tariffs are in an interesting position from the perspective of Functional Finance (a perspective that has been revived by Modern Monetary Theory). A key principle of Functional Finance is that central government taxes are not for revenue, rather for inflation control. (I discuss this in earlier books.) We do not have much modern experience with significant tariff policy changes, but I can outline what are the theoretical effects.

In a steady state, tariffs drain income flows from the private sector, and so should be fungible with other tax revenues from an inflation control perspective. They are a regressive tax, and so might have a more dampening effect on growth than more progressive taxes (since their effect falls upon cohorts with a high propensity to spend). However, dynamical effects are not helpful for inflation control.

If tariffs are raised, there is a one-time shock to the price level. As seen after the pandemic, people in the real world have a hard time distinguishing between one-time price shocks and continuing inflationary forces. That is, the one-time shock might feed into continuing inflationary psychology.

If there is a reallocation of the share of nominal spending away from the goods effected by the tariffs, they will have less of a dampening effect on domestic demand. Obviously, if there is a substitution away from imported goods (the objective of the industrial policy justification, to be discussed later), capacity utilisation in the domestic economy increases, putting upward pressure on prices (although one can have theoretical quibbles about the exact mechanisms involved). Increasing tariffs on foreign goods will not do much to cool spending on domestic services, real estate, and construction — major components of modern economies.

Concluding Remarks

The discussion in my next article will swing to the more conventional justification for tariffs — saving manufacturing jobs.

References

The Long Shadow: The Legacies of the Great War and the Twentieth Century, David Reynolds, Simon and Shuster, 2013.

My books “Understanding Government Finance” and “Modern Monetary Theory and the Recovery” discuss Functional Finance.

If you want to see how silly the “present 10 years worth of revenue as a dollar amount” framing is, total Federal revenue would be $51,000,000,000,000 over 10 years if revenues did not grow (which they would, since the economy is expected to grow in nominal terms).

There’s probably a third reason for tariffs, which is likely the actual reason in this case - to reduce the amount the FX nation is financially saving in your denomination.

IMO the main event is the 10% global tariff. Everything else is a negotiating position.

Under a floating exchange rate system the net effect of this tariff should be to move financial saving from abroad to onshore as there is no reason for, say, Canadian lumber to exchange for, say, more or less US plastic than it did before. Trade between currency areas being ultimately a productivity play, not a financial one. (That's not to say that the prices and wage rates won't shift and change the individual distribution).

Real exports exchange for real imports, directly or indirectly, at 'world prices' even if you don't have a currency at all.

Because the U.S. federal government is Monetarily Sovereign, it neither needs nor even uses revenue. It destroys every dollar it receives and pays its bills with newly created dollars ad hoc. Even if the federal government collected $0 in taxes and other revenue, it could continue spending forever. That is the fundamental difference between federal government financing and state/local government financing. The former is Monetarily Sovereign. The latter is monetarily non-sovereign.