Treasury Market Pricing

The Fed surprise 75 basis point hike last week blew Treasury yields out, with a small reversal at the end of the week. Such a reversal is typical after large moves. In this article, I just want to discuss the big picture of Treasury pricing.

The figure above shows the post-2000 history of the 2-year Treasury yield. What we see is that the rise in yields in 2020 has been extremely violent when compared to previous behaviour. This fits in with market commentary pointing out that Treasuries have seen the worst short-term drawdown in decades.

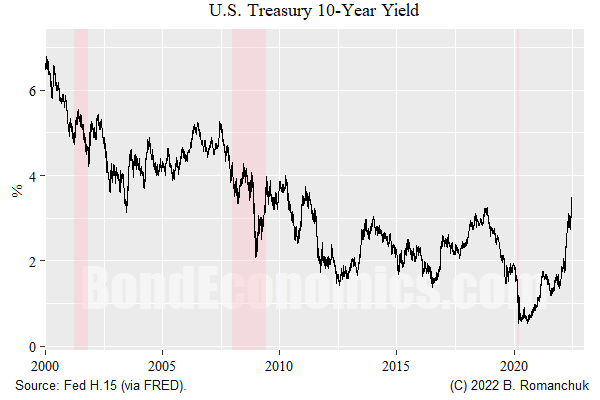

The figure above shows the history of the 10-year yield over the same period. In this case, we can see that the recent move is still large, but its past history shows more volatility.

Risk-free rates are literally the simplest instrument to price in finance, and so the rates market ends up being closer to the theoretical ideal of “efficient markets”: rapidly changing price as new information comes in. If we eyeball the 10-year yield, we see that there are periods of range-trading that end with rapid movements to new levels. This behaviour is the worst possible behaviour for technical analysis, since mean-reversion trades are punished during the violent moves, and trend-following is punished when range-trading. This is somewhat different to commodity, equity, and foreign exchange markets — since “fair value” is somewhat nebulous, we quite often run into trending behaviour.

If we go back to the 2-year yield, it does appear to follow trends, with the recent experience being an outlier. This was the result of “gradualist” interest rate policies. The Fed used to be in one of three modes: on hold, hiking by 25 basis points per meeting, or cutting rates in a panic. As such, most of the time, market pricing for the Fed tended to be correct — it was only transition between “modes” that changed pricing dramatically. As such, most profits/and losses versus forwards were concentrated in short period when the mode being priced shifted.

The current rise in the 2-year rate was more rapid since the market pricing was wrong-footed from two directions: the terminal rate was rapidly revised higher, and the pace of race hikes is double (or triple!) that of recent cycles.

In other markets, the tendency to get increasingly bearish as prices fall can be rewarded at times. Should we extrapolate past losses forward? The issue here is that we need to keep in mind the simplicity of rates pricing. To keep moving the 2-year, we need to keep pushing up the Fed’s terminal rate. Is this plausible?

Recession Calls Everywhere

I do not follow street research, but I am seeing a drumbeat of recession calls on economics/finance Twitter. I certainly have sympathies for a recession call — but I remain cautious about the United States/Canada (as opposed to other countries with worse energy supply outlooks). Recession risks are the main obstacle for bond bearish positions: it is hard to see the Fed hiking to 4-5% if the global economy implodes in the next couple of quarters.

The 2-/10-year slope snapped back on Friday, but it is flirting with inversion. Although economists love to discuss the 2-/10-year slope as the result of the bond market pricing recession odds, it is the spread between two pricing benchmarks. Bond investors get paid based on trading profitably, not whether recessions are declared.

The current situation is a bit hard to interpret. The reason for a near-run inversion is that the 2-year is pricing another slug of rate hikes. If we are to take pricing at face value, all that is expected to happen is that there would be a small reversal of rate hikes in a couple of years.

Such an outcome is not impossible, but I believe it is only consistent with a “soft landing” scenario: the Fed hikes rates to around 3%, inflation is tamed, and there is no recession over the next year. Otherwise, one benchmark or the other is wrong: the Fed keeps hiking rates to contain inflation, or we have a hard landing and they are forced to cut. The bond bears are attracted to shorting the 2-year, and the 10-year is attracting the bulls.

One theoretical wrinkle on the “yield curve predicts recessions” debate is a scenario of a very rapid meltdown in activity. If it happened soon enough, it could take out a lot of the priced rate hikes — steepening the curve ahead of a significant inversion. I am not convinced that this will happen, but it is clear that it could happen.

War and Commodities?

The situation on the ground suggests that there will not be a rapid end to hostilities, as the Ukrainians have indicated multiple times that they intend to counter-attack on a greater scope towards the end of the year. Until the fate of that counter-offensive is known, there will be no serious peace talks.

Even once fighting reaches a lull, it would take time to formulate a peace deal — assuming that both sides are interested in a deal (which could easily not be the case). As such, the commodities markets will be disrupted for some time.

We should see greater rail transport of Ukrainian wheat going forward, but that will take time to organise. Russian oil appears to be making its way to market via third countries. As such, it is possible that the oil situation has entered into a new steady state. Natural gas piped into Western Europe seems to be the main uncertainty in the near run. Over the longer term, if Russian supply is shut it, their long-term production capacity needs to be revised lower.

As such, it is hard to see too much relief for global energy prices in the absence of more meaningful demand disruptions.