Although neoclassical macroeconomic theory does its utmost to obfuscate matters, monetary policy in practice is straightforward: central bankers react with a lag to economic data, and if they are panicked about inflation, they hike rates until something breaks. Although that description is more flippant than how conventional economists would describe the situation, it probably represents a consensus view. However, there is a hidden complexity: do things “break” because of rate hikes, or do they break on their own?

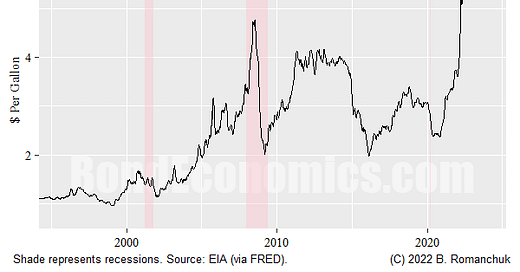

As the figure above shows, we are in the middle of commodity prices going parabolic, which is a typical mode of behaviour. I showed U.S. diesel prices, as refined products are in the worst shape in the petroleum complex. On a forward-looking basis, one of the three things must happen.

Petroleum prices continue to go parabolic. However, this scenario will eventually cause something to blow up. So far, the United States and Canada can absorb the higher prices (with a great deal of grumbling), but other countries are in a more exposed position.

Energy markets have reached “equilibrium” and will remain at a “permanently high plateau” near current levels. As the chart above shows, energy prices do enter periods of steady prices, they tend to have violent corrections in response to rapid rises.

Price violently correct to lower levels. They might bottom at higher levels, but there would be at least some relief in terms of the rate of change of prices.

The typical pattern of oil prices is to overshoot and violently reverse. Given the detachment of trading behaviour from fundamentals, I would have no confidence in peak price predictions. Instead, I think the forecast challenge is more time-based: how long until something blows up?

My view is that the main effect of policy rate changes is via the effect on the housing market. The fundamentals of the housing market are relatively slow moving, which means that I expect the oil price spike to reverse long before the housing market slows as a result of rate hikes.

Yeah, Bond Markets Probably Moving to Price a Recession

The 2-/10-year slope is relentlessly flattening, being on the verge of inversion territory at the time of writing. Flattening is entirely typical behaviour during a rate hike cycle — the long end does not rise one-to-one with the policy rate.

Recent years have been filled with plenty of silly articles on the lines of “the 17.5-year to 22.75-year Treasury has inverted — bond investors are pricing a recession!” Unlike the random slopes that people have thrown up as examples, the 2- and 10-year are benchmark maturities that are significant for pricing. A deep inversion would correspond to a significant reversal of Fed policy, which would typically happen around recessions.

The thing to be cautious about is that the recession need not happen in the United States. Even though the Fed is domestic-oriented, falling demand elsewhere would cool financial markets and create spare capacity.

At the time of writing, crypto markets have been battered as people once again discover that expecting non-audited entities to keep their liabilities pegged at par is not perhaps the most sensible strategy. Crypto by itself is macroeconomically insignificant, but it is correlated to tech equities. The stock market is not a totally reliable recession indicator. This is particularly true for the tech sector, where valuations bear no resemblance to real economic activity. That said, falling risk asset prices tends to pressure credit spreads — which do matter.

What Will Give?

To get the Fed off the rate hike path, something has to give. The challenge is guessing where the weak link is. I will run through the major candidates in order of severity.

The “soft landing” scenario is that the inventory correction (which is showing up in the data) as well as demand destruction will cause a reversal of price pressures. This is without too many major economies going off the rails. This was essentially the consensus scenario up until the end of 2021 (at least).

Weak link economies give. Economies that are less able to absorb the commodity price shock will go into recession, which then bounces around the globe. Given that many developing economies also have difficulties with rising U.S. dollar interest rates, that is probably where one would expect problems. European economies are also generally more exposed to the energy crisis. This would probably be my base case if I had to wear a forecasting hat.

The U.S. domestic economy is dragged into a correction courtesy of the inventory whipsaw, the commodity price shock, and slowing housing markets. I am somewhat unconvinced by this possibility, as I expect that weakness would be transmitted from elsewhere.

A financial crisis that freezes credit markets. (I do not consider falling equity markets to be a financial crisis, and falling crypto prices would just be a source of amusement.) Although some financial systems might be weakened by recessions, there are no major default sources on the horizon that would be sufficiently large to take out the major global banks. As such, I lean towards financial difficulties being in equity markets as well as isolated bankruptcies.

Macro Theory — Limited Help

Finally, I want to emphasise the limited usefulness of mathematical macro theory. The only place where such a theory would have been of use is giving a better inflation forecast in 2021. Given that “transitory” was the base case for central bank economists (as well as being close to a consensus view). it is clear that the conventional models were not entirely helpful. (The growth industry in the next few years will be the rise of people who were inflation bugs last year.)

At this point, worrying about the innards of inflation is a secondary concern relative to the “will anything break?” question. Things blowing up is a balance sheet analysis question, and we need to focus on the weak link entities. This is not an area of strength for aggregated macro models. To what extent they will work, it is because we dodge potential crises.

The other theoretical angle is that Fed rate hikes would be blamed for any crisis that pops up — even though the policy rate is unlikely to get to any plausible estimate of “neutral” over the coming year.

Spot on and amusing at the same time.