This article is a complete re-write of two existing sections of my manuscript. I was unhappy with the sections, and they were blocking my progress. I decided to throw in the towel, and just cut the text down to the minimum. The text probably needs work, but it is no longer going to be black hole for revisions.

The beauty of the Cantillon Effect is that it gives a simple relationship between inflation and financial asset markets. Allegedly, people who somehow get “new money” first rush out and buy financial assets, driving up their price. This then leaks out into consumer prices. The problem with simple rules related to financial asset prices is: why are the people who discovered them all getting rich using them?

Complicating matters is that different financial assets behave in different ways in response to inflation trends. Since the author does not believe that there are any magic ways to make money in most financial markets based on inflation forecasts, I will just offer general comments on differing asset classes.

Inflation-Linked Bonds

The one market where one can use correct inflation forecasts to make money is the inflation-linked bond market. I discussed this market in my book Breakeven Inflation Analysis. The catch with inflation-linked bonds is that being correct about inflation over the next few months may or may not matter for profitability, you theoretically need to be right about the forecast until the bond matures. Given that inflation-linked bond trading is the domain of specialists, I will just refer readers to that earlier book.

Commodities

Another relatively straightforward asset class are industrial and soft commodities (like grains). Energy price spikes are often associated with spikes in overall inflation rates. If there are supply shortages on a global scale, it is likely going to show up in commodity markets. Hence, commodity prices rose in the 1970s as well as after the pandemic.

Where things get trickier is away from such spikes. The old trader adage in commodity markets is that “the cure for high prices is high prices.” If there is a price spike in a commodity leads to finding alternatives to consuming that commodity, as well as bringing in new sources of supply. We can then see a grinding bear market as the excess of supply is wrung out. This process is largely a global phenomenon, while countries may have their local economies overheating for whatever reason, leading to rising inflation despite commodity price weakness. (This was the experience of the mid-1980s and 1990s.)

Gold

In the Gold Standard era, owning gold was a straightforward way to preserve purchasing power against inflation. But once President Nixon closed the Gold Window in 1971, currencies have been de-linked from gold. It is very hard to see how a return to linking currencies to gold matters for any major economic power. Nevertheless, there is a noisy contingent that fantasises about a return to gold, and the gold market can respond to inflationary vibes.

The figure above shows the gold dollar price from 1990-2018, which captures the end of the secular bear market, as well as the upswing that started in the early 2000s. The bear market followed an earlier bubble that peaked in the early 1980s, as well as central banks slowly unloaded their gold reserves, replacing them with interest-bearing bonds.

Gold is an unusual commodity in that gold consumption (such as making jewelry) is quite small when compared to gold held in inventory. The primary determinant of the price of gold is how it is valued versus other assets, and physical supply and demand is secondary. As a financial asset, its value is somewhat of a puzzle: it costs money to store, while generating no cash flows (without lending it out). As such, its value is driven by “animal spirits” among gold traders (including central banks).

If we look at the above chart, it is hard to see a clear link with inflation. The 1990s was the decade where inflation generally converged towards inflation targets in the developed world, yet gold slowly lost value. The bull market starting in the early 2000s did not correspond to an uptick in inflationary trends. One might be able to massage the data to discover some short-term relationship, but such relationships tend not to persist.

Bonds

The high-level relationship between bond yields and inflation higher inflation tends to result in higher bond yields. (Note that the price of a bond moves inversely to the yield, so a higher yield means a lower price.) The difficulty is that the relationship is less mechanical than market folklore suggests. This relationship relies on central banks acting in a conventional manner. For example, it is possible for the central bank to peg bond yields, breaking the correlation.

The best way to understand bond yields outside of market crises is that they represent an “average” guess of bond market participants for the path of the overnight rate, which is controlled by the central bank. In turn, the central bank is attempting to control inflation by raising and lowering the policy rate. As such, the relationship between inflation and bond yields is that the bond market reacts to data that is likely to cause the central bank to move the policy rate – and the inflation rate is an important variable. However, inflation tends to lag the business cycle, while bond market participants are supposed to be ahead of the business cycle. As such, statements to the effect that the bond market must react to an inflation release misses the reality that the inflation news may have already been built into the market pricing.

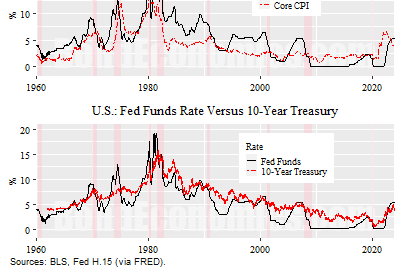

The reader is free to squint at the charts above to validate my claims. The top panel shows U.S. core inflation and the overnight (Fed Funds) rate. We can see that the overnight rate does tend to follow inflationary peaks – although inflation was relatively flat in 1990-2020, yet we have policy rate cycles. The second panel shows the overnight rate (again) and the 10-year Treasury yield. The relationship is perhaps less obvious, but it makes more sense if bond market investors tend to expect the policy rate to revert to historical averages. In the 1980-2020 period, there was a sustained downtrend in the policy rate, while the bond market discounted a reversion towards earlier levels (which did not happen until the 2020s).

Since bond prices are moving in an inverse fashion to inflation, the Cantillon Effect does not apply to bonds.

Equities

Equities (and real estate) are usually what people are thinking about when discussing the Cantillon Effect. Although it is possible to see some plausibility to the concept, the problem is that guessing where equities will go is necessarily challenging – you are competing against a lot of other investors attempting to do the same thing.

There are two broad ways of analysing equities.

You buy equities if you think you can sell them to somebody else at a higher price relatively quickly. (Where “relatively quickly” depends upon the investor and can range from milliseconds to a couple of years.)

You do not try to guess what other people will pay for equities. Instead, you just buy if you think the underlying companies will generate enough profits/cash flow to justify the purchase price in the long run.

The difficulty with equity analysis is that there is only one long run, but plenty of short runs. As such, equity analysis is dominated by analysing what happens over the short run. Unfortunately, equity investors in practice are unhinged, and any number of crazy things can happen over the short run. If equity investors are convinced that “money printing” can cause equity prices to go up, there is very little to stop them if so-called “money printing” happens.

The Cantillon Effect story is misleading in that it seems to imply that “money printing” is something external to the equity market. The equity markets are not static, waiting for outside money to flow into it. Equity market participants can adjust prices instantaneously in response to news (e.g., a bad earnings report), and can use leverage (either by borrowing or using derivatives) on their own if they believe that equity prices are about to rise. Using flows to explain equity prices runs into the accounting reality that for every buyer, there is a seller (or else someone in the back office is going to have a bad evening). In other words, what matters is the belief about “money printing,” not the actual “money printing.”

On the fundamental analysis side, inflation has a somewhat mixed effect. To the extent that higher inflation pushes up interest rates, the discounted value of future cash flows drops. This is countered by the hope that firms will be able to raise prices in line with inflation, raising the nominal cash flows of the firm. (If both revenue and expenses scale by the same factor, profits are also scaled by the same factor.) Meanwhile, higher inflation is typically associated with faster growth of the real economy – which is beneficial for profits. As such, it is not incredibly surprising that both equity prices as well as the price level tend to rise during an economic expansion – and reverse during recessions.

Concluding Remarks

Commodities, real estate, and equities are pro-cyclical and we should therefore expect them to benefit from an economic expansion. Inflation is also pro-cyclical. As such, we should expect a correlation between those asset classes and inflation.

"the central bank is attempting to control inflation by raising and lowering the policy rate."

I am increasingly struggling to find empirical evidence that this actually works, but I suppose for investment purposes it is sufficient that most market participants (and central bankers themselves) believe that it does?