Disinflation Needed A Lot Smaller Than Early 1980 Case

Marijn A. Bolhuis, Judd N. L. Cramer, and Lawrence H. Summers released a NBER working paper “Comparing Past and Present Inflation” (link) which constructs a alternate CPI index that is comparable to the present methodology. Historically, the housing component was based on house prices and included mortgage rates — which meant that the housing component of CPI mechanically follows interest rates.

During the Volcker Madness, this meant that the rapid rate hikes drove up CPI and then CPI inflation fell after rates were reversed. This effect makes the Volcker policy appear more disinflationary — since it first raised peak inflation, then the effect reversed.

Although the alternate CPI is of interest, this is only if one is interested in the Post-World War II and Korean War experiences. Since many commentators have drawn comparisons between the current inflation episode and that earlier era, this is not a trivial thing. However, for discussing the Volcker experience, we can just use the Personal Consumption Expenditure (PCE) deflator — which is revised to have a consistent methodology over time. (Since contracts and benefits are indexed to the CPI, it cannot be revised.)

Close to the 1970s?

The housing analysis within the paper is of interest, since it relates to a topic that is popular with CPI conspiracy theorists: house prices being dropped from the CPI, to be replaced by rents. However, I will have to look at that part of the paper later. Instead, I want to react to one assertion in the paper:

First, our observations imply that the current inflation regime is closer to that of the late 1970s than it may at first appear. In particular, the rate of CPI disinflation engineered in the Volcker-era is significantly less when measured using today’s treatment of housing. In order to return to 2 percent core CPI today, we need nearly the same 5 percentage points of disinflation that Volcker achieved.

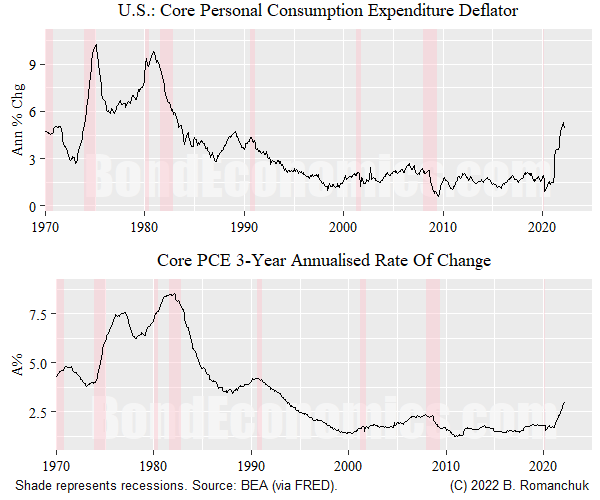

If we look at the core PCE deflator, this does not really hold up.

Core PCE annual inflation registered 4.9% in April, and so we need a 3% drop to return to 2%. If we look at the back history, we see that there were two historic disinflations since the 1970s of such a magnitude in roughly a one-year span.

Core PCE inflation dropped from 10.2% in February 1975 to 6.0% in May 1976 (a 4.2% drop).

Core PCE was 9.8% in January 1981, and dropped to 7.0% in March 1982 (and kept falling).

As seen by the recession bars, those disinflations coincided with recessions. Absent a recession, I see very little chance of a similar disinflation in core (although headline inflation might get whacked at some point due to a oil price whipsaw). So if the authors’ intention to solely focus on an immediate disinflation, we might need extremely aggressive rate hikes to cause an immediate deep recession.

Realistically, that is not an option embraced by policymakers — they accept that a disinflation will take time. This is particularly true for the housing component of the CPI (which has a considerable weight in core CPI), as its construction creates considerable lags — it is nearly impossible for it to turn on a dime.

Nevertheless, the belief that we are “close” to the 1970s inflation regime is hyperbolic — as the bottom panel demonstrates. The mid-1970s disinflation episode is usually ignored — since inflation persisted at a high level. The bottom panel shows the annualised inflation rate over a 3-year horizon (which covers the inflation drop then spike since the pandemic). Yes, the current reading is high — but nothing like the ever-rising pattern of the 1970s.

By the early 1980s, most developed countries (with a few exceptions) had been fighting a losing battle with inflation for a decade or longer. Inflation psychology was ingrained. Although inflation did not subside as quickly “Team Transitory” (although not a forecaster, I was a sympathiser) expected, 2022 is in a much better place than 1980 with respect to inflation.

CPI Versus PCE Deflator

The authors offer at least three reasons to prefer their constructed CPI, I am only convinced by one.

Since the PCE deflator starts in 1959, we need some form of experimental series to cover the Korean War and WWII demobilisation. Although the analogy to that period has merit, I am unconvinced that we can ignore the institutional changes that have happened since that era.

CPI is used in indexation, which has cash flow effects. This is true, but to take this into account, we need to look at historical headline CPI — since that is what is used in indexation. If we are looking at experimental series that are supposed to measure “true” inflation better, we have to accept that they do not correspond to anything observable in the historical economy. In which case, CPI has not privileged position versus the PCE deflator.

CPI has a greater psychological impact. However, if we are concerned about psychology, we need to look at headline — gasoline and groceries are the main topics of popular inflation discussions.

Concluding Remarks

Although the article has interesting content, some of the glib textual assertions inserted into it are somewhat suspect — and the odds are that those assertions will be the ones broadcast in popular discussion.