Canadian Data Roundup

The Bank of Canada remains hawkish (by modern standards), and the policy rate is marching higher. Unless there is a surprise slowdown in inflation (or activity), the policy rate is on track to hit 2.5-3%. As the figure above suggests, that might be enough to get the 5-year Government of Canada yield to break above its highs for the post-Financial Crisis period. The 5-year is already pricing in rate hikes, and so the more bond-bearish commentators might be angered by the lack of one-to-one movement in the overnight rate and the 5-year rate.

The 5-year Government of Canada rate matters as it is the benchmark for 5-year mortgages. The structure of the Canadian mortgage regulation pushes most borrowers into a 5-year mortgage. (The mortgage amortisation is typically 20+ years, but the interest rate needs to be re-negotiated at the end of the fixed term.) Rising mortgage rates ought to cool some of the exuberance in the housing market — but I doubt that it will not much more than a cooling down so long as the 5-year rate stays below 4%.

Financial commentators (outside bank economists) take an alarmist stance towards Canadian housing. As someone who has been bearish on Canadian housing for a very long time, I emphasise that one should not expect an immediate collapse. To what extent that rate hikes cool the housing market, they will also take some demand pressure off the economy. This will not be enough to do anything about gasoline prices or internationally traded goods, but domestic pricing power might fade. The Bank of Canada knows that if housing implodes we will be facing a deep recession, so they know that they cannot mindlessly hike rates based on lagging data.

I have been hit with a burst of consulting work, so I will just run through some Canadian data.

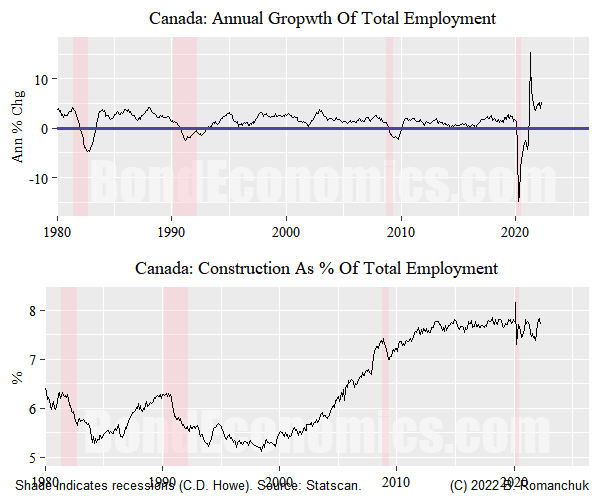

Although things could change, employment growth remains strong in Canada. The top panel of the above chart shows the growth of total employment. The pandemic caused data chaos, with a spike up and down. Although the initial surge is over, annual growth is still around 5%. This almost certainly has to slow, but that is not saying much — it is still around peak growth rates in the post-1980 period.

The main macro vulnerability created by housing revolves around construction employment. The CMHC (a Crown Corporation that has a full faith and credit guarantee by the Government of Canada) has generously underwritten the credit risk posed by mortgage defaults, so Canada does not face what happened to the U.S. financial system ahead of the Financial Crisis.

Starting in the year 2000, construction was the driver of employment growth. As seen in the bottom panel of the above figure, construction employment grew faster than overall employment, and its share of the total grew. However, that outperformance has peaked, and construction share of the total remains at high (permanently high?) plateau — with some wiggles around the pandemic.

The above figure shows the 3-month average of monthly housing starts, which is a horribly seasonal series. I would expect some cooling, but the question is whether it just ends up near the average of the 2000s.

Although I am a Canadian homeowner, I am unconvinced about the value-added of worrying about house prices. Higher interest rates will mechanically put downward pressure on house prices, since households tend to be near their borrowing capacity limits. Perhaps condo speculators in the big cities might take a bath, but I am unconvinced how much that would matter for the overall economy.

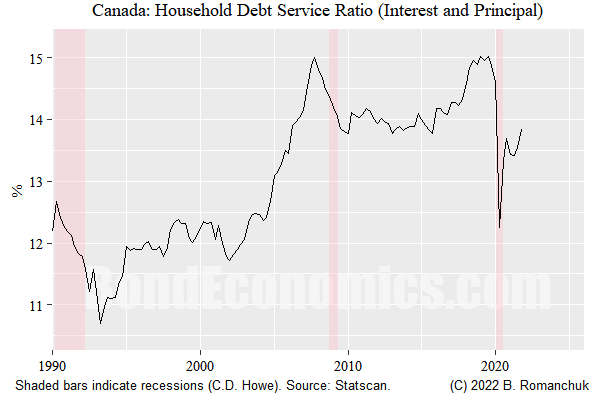

Although everyone loves to show the debt-to-income ratio of Canadians, such charts ignore the effect of lower interest rates. Historically, Canadian houses were cheap, outside of Toronto and Vancouver. Extremely cheap versus England, and even versus the United States — since there is no mortgage interest deduction. As such, debt service levels were low in the 1990s (even with higher interest rates), but that was ended by the the relaxation of CMHC standards. Even so, the current debt service burden looks that it will end up close to where it was in the previous decade (so long as rates do not rise by hundreds of basis points).

Concluding Remarks

Canada is a commodity exporter, and so even though I am concerned about the impact of the commodity price spike on Europe, Canada is positioned to muddle through. Although an aggressive Bank of Canada poses obvious risks, everyone over-estimates the power of interest rates. This exaggerated fear will help keep the peak policy rate at levels that can be absorbed by households.